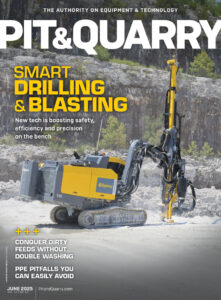

Percussive drilling differs entirely from rotary drilling.

In percussive drilling, rock is caused to fail by imparting a sharp blow onto a bit and using a rotation device to turn the bit a sufficient amount to keep it indexed to cut a circular path. The rotation in percussive drilling is best kept to a minimal value, and feed or down pressure should be sufficient to keep the bit fed to the bottom of the hole.

In rotary drilling, no blow is struck and the rock is made to fail by a combination of down pressure and rotation speed. In blasthole work, the cuttings are flushed from the hole by compressed air, but consideration here is more toward providing enough volume to maintain a suitable bailing velocity rather than pressure.

Rotary drilling, then, is more of a brute-strength operation, requiring massive pull-down systems and raw rotation power.

Still, with a suitable high-pressure air supply, a rotary drilling machine can be used with down-the-hole drills should the conditions dictate.

Because the principles are different, it stands to reason that bit design for rotary drilling differs from that of percussion drilling. For blasthole rotary drilling, bits usually take two configurations: drag or blade bits, and roller cone bits.

Bits of information

A drag or blade bit has fixed wings that penetrate the rock and gouge it out.

Some of these bits are supplied with replaceable blades. For harder materials, the blades are tipped with tungsten carbide for longer wear life.

These bits are generally confined to soft formations – usually less than 20,000 psi compressive strength – and in smaller diameters in the range of 3 1/2 in. to 6 in. Their rigid design prohibits the metallurgy from withstanding the higher pull-down and rotation stresses necessary in harder formations and larger diameters.

Roller cone bits, meanwhile, are highly utilized for blasthole drilling.

A bit consists of three conical-shaped members that rotate on a combination of roller and ball bearings. Mounted on these cones is a cutting tooth design that’s dependent on the hardness and compressive strength of the material being drilled.

On some of these bits, the teeth are cut on the cone body itself for softer formations, whereas for harder rock, the cutters are hardened steel or tungsten carbide inserts.

The tooth patterns on adjacent cones complement each other so they contact different portions of the rock. On some bit designs, the axes of rotation of each cone are offset from the others to impart a scraping action to the material to be drilled.

One critical point of any roller cone rotary bit is the bearings. In addition to failure due to excessive pull-down or bit loading, these bearings must be kept cool and clean in an otherwise hostile environment.

A sufficient amount of compressed air should be delivered through the drill pipe to the bit to properly flush cuttings from the hole with a suitable bailing velocity. In addition, a portion of the air must be diverted through passages in the bit body to clean and cool bearings.

While air pressure is of less importance in rotary drilling, it is vital that sufficient pressure be delivered to a bit to perform the cooling-cleaning function.

Related: P&Q University Lesson 4: Drilling & Blasting

Information for this article was adapted from Pit & Quarry University.