Whitaker Contracting is a third-generation family-owned business in Guntersville, Alabama, and it’s been around for almost 60 years. In addition to its aggregate operations, the company does site work, subdivisions, roadway and airport projects, and more.

“We build buildings, and we do a lot of paving work for the Alabama Department of Transportation,” says John Davenport, company project manager.

Davenport started in the business before electronic distance meters.

“I remember when we pulled a steel tape,” he says. “We used plumb bobs.”

Davenport has had an opportunity to see a lot of changes. Regarding how technologies such as drones affect our day-to-day life, Davenport says it’s like asking what it was like before cell phones were around.

“How did anyone get around before there was a car? That’s the level at which it impacts us,” he says.

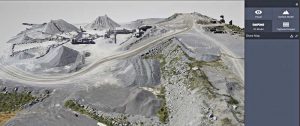

“Today when we get a job, I can go in and build a 3-D model of it [with a drone],” Davenport adds. “We can then load it into a dozer and it gets real-time coordinates, so the dozer goes out there and knows exactly where it’s at and cuts to grade, etc.”

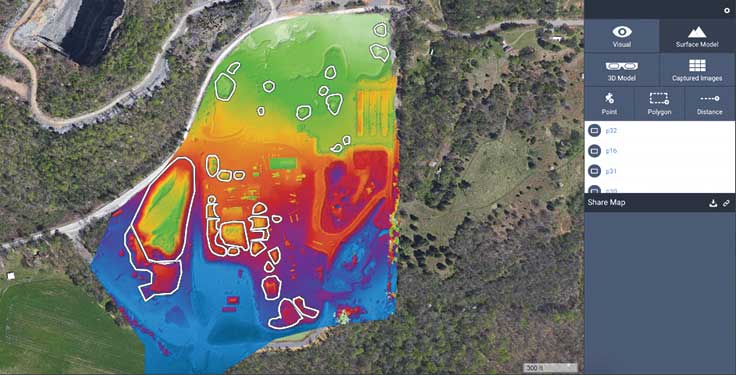

Davenport tells a story of how he calculated the volume of a stockpile of topsoil at a construction site using the most up-to-date survey equipment available. He then flew a drone over it and came up with a figure differing from his original estimate by only one half of 1 percent. When he realized what caused the difference in the numbers, he began to believe the data from the drone was more accurate than even his survey-grade data.

Aggregate stockpiles

Davenport takes the drone out and puts up a geo-fence to define the area he wants to capture.

“I tell it how high I want it to fly, and I tell it how sharp I need the imagery. That controls how many photographs it takes.”

The drone calculates its own flight path based on the geo-fence and other variables. After the flight, the data is downloaded to an iPad on site.

Davenport notes that this process is much safer than manual stockpile measurement.

“At our quarries, we have areas where we reclaim water, and there’s always a possibility of falling into that,” he says. “On construction sites, we have heavy equipment running back and forth, but we have to go into these environments to survey the points to do volumetric comparisons and accurately figure out our estimates for payment. There’s quite a bit of liability when you’re walking around out there. It’s really dangerous.”

Davenport suggests spending some time with the technology.

“Think through how it can serve your needs,” he says. “There are drones that will do all sorts of stuff that probably isn’t geared toward what you’re doing. Focus on what you think will work.”

That was the approach Davenport took as someone who was skeptical about the technology.

“I mean, I’m not trying to design the Empire State Building,” he says. “I want to take care of volumetrics because we’re moving materials all the time.”

Information for this article based on an interview conducted by Jeremiah Karpowicz, executive editor for Commercial UAV News.