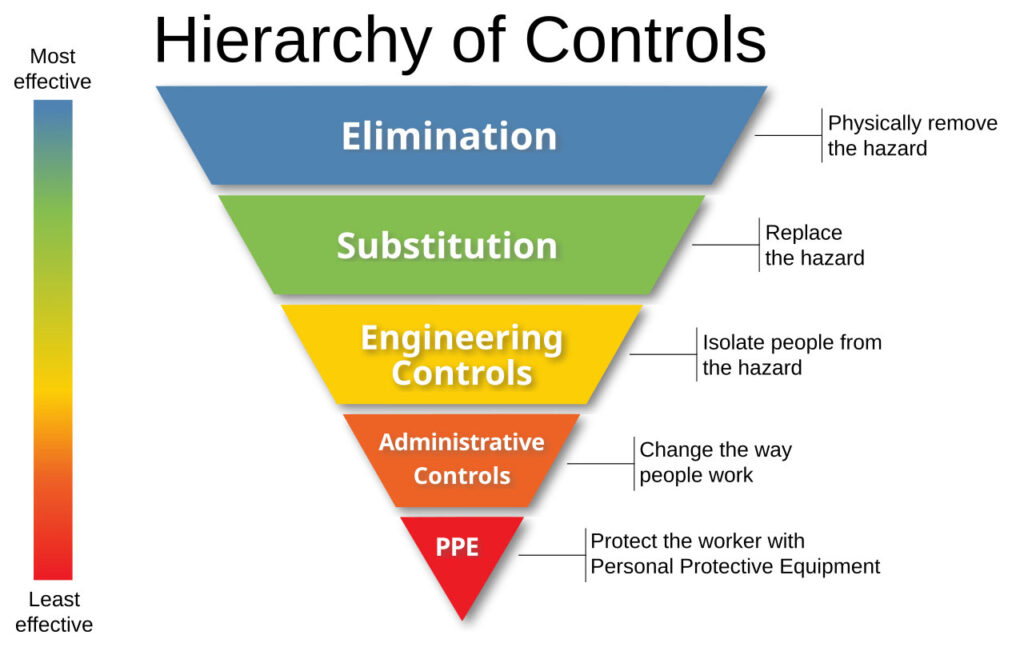

Over the past year, this column has referenced the hierarchy of controls nearly every month. While I’ve outlined the intent of this upside-down triangle (seen below), we’ve only done so in passing. This month, let’s dive a little deeper into this powerful tool.

What is it?

Regardless of the industry, safety is rooted in hazard identification and hazard control. If organizations manage those two elements well, people go home safely every day.

The hierarchy of controls helps us control hazards more effectively. It’s one of the most fundamental aspects of creating a safety culture.

Understanding the triangle

The first thing to do when examining the hierarchy of controls is look at the bar on the left – it points you in the direction you want to go.

The bottom of the triangle (PPE) is the least effective, primarily because it relies on humans to remember to wear and properly use protective equipment. The top of the triangle (elimination) is the most effective and requires the least amount of human interaction for sustainability.

Here’s a simple example to help you better grasp the upside-down triangle. Let’s go with the hypothetical of someone slipping off a ladder used to access an elevated work platform to lubricate rotating machinery. As we go through the scenario, think of the analysis as being like peeling back layers of an onion – until we get to the most reasonable solution.

PPE

This is the most basic control. Some investigations may stop at this point, but that’s a mistake. This would sound like: “To prevent recurrence, the employee should wear shoes with better tread.”

As you can imagine, this falls short of great prevention and pretty much places blame rather than preventing recurrence.

Administrative controls

This control is all about minimizing exposures but not necessarily controlling them. This would sound like: “To prevent recurrence, the employee should only access this elevated platform once a month to lubricate the grease points.”

You can see this effectively controls when the exposure occurs, which may raise awareness and help a little – but doesn’t fully address the hazard.

Engineering controls

This is where we begin to isolate people from hazards. In our example of someone slipping off a ladder to access a lubrication point, action would sound like: “To prevent recurrence, grease points should be piped in at ground level, eliminating the need to access elevated work platforms altogether.”

This is a very effective approach.

Substitution

Substitution is basically replacing something hazardous with a safer alternative. This is a common control to use when working with chemicals, and you can use different chemicals that are less hazardous.

In our example of slipping off a ladder, action may look like this: “To prevent recurrence, ladders should be replaced with stairs.”

This is also a very effective control, particularly if engineering alone won’t mitigate the hazard.

Elimination

Executives reading this should push their organizations to get to this level. While it may not always be possible to eliminate hazards, eliminating them should be the goal.

In our example, action would look like this: “To prevent recurrence, operations will work with the manufacturer to move toward sealed components not requiring lubrication.”

As you can surmise, this is a difficult control to fully implement. But if elimination is the goal, you increase your chances of getting as close as possible.

How to use this

So what should organizations do with this?

I have three recommendations to integrate the hierarchy of controls into your organization:

1. Incident Investigations. In one organization I supported, we reviewed every motor vehicle event and every injury as a team. At the end of every incident review, we put the hierarchy of controls on a screen and discussed how far we got up the triangle. It helped us avoid stopping at the first layer of the onion.

2. Communication. In another organization, we put the triangle all over the place – in newsletters, in briefings, in 3-ft. decals in training rooms, in stickers on hard hats and in other places. This inundation helped make this part of the company’s vernacular.

3. Alignment. Getting the safety committee, safety pros, ops leaders and executives on the same page created alignment. Misalignment lies at the root of many failed initiatives. Executives should always be on the lookout for it and take steps to correct it.

Leadership tip

Make stickers out of the triangle. Put one on something you’ll see frequently – your laptop, your notebook, somewhere in your office.

Seeing the image will help steer you toward practicing its principles each and every day.

Finally

It has been my pleasure to write this column for the industry over the past 14 months. I hope you’ve enjoyed it this year and that you’ve taken some practical tips from it.

If you ever need help solving challenges on your safety journey, don’t hesitate to reach out.

Steve Fuller has worked over the past 20-plus years with a variety of industries – including aggregates – in operational and safety leadership roles. Now representing Steve Fuller Company, he can be reached at steve@stevefullercompany.com.

Related: Strengthening safety around mobile equipment in quarry operations