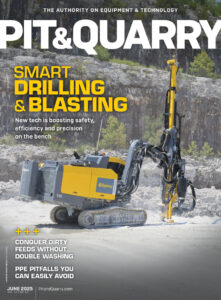

The debut of the new Pit & Quarry University Handbook offered an opportunity for P&Q to visit with Anthony Konya, an explosives engineer within the industry. Konya recently joined Episode 55 of Pit & Quarry’s Drilling Deeper podcast to explore core drilling and blasting concepts, reflect on lessons learned from the field and to explain how fast-evolving tools are reshaping quarrying. The content that follows is an edited excerpt from that conversation.

In the handbook, you call blasting the ‘first transformative act’ in quarrying. Why? And how does blasting set the tone for everything that follows?

Konya: My view of the quarrying industry – and now, having been a quarry owner across multiple states – is that we’re an industry that takes really big rocks and makes them into really small, well-sized rocks. To do that, we have to start with what Mother Nature gives us and turn it into something that can go through a primary crusher. Blasting is the first part of that.

Blasting is also the one process that has essentially infinite reduction. You go from solid rock to material that, in some cases, is as fine as dust. So it’s the primary process, but it’s also the process that has the biggest potential impact on everything downstream when we’re trying to make big rocks into small rocks.

If we have a poor blast and we’re feeding a lot of oversize into the jaw, it’s going to drastically impact that crusher – the maintenance, the productivity, everything. That larger rock then goes into the cone, and now you’re slowing that down, changing tons per hour, hurting productivity. Over and over again, a bad blast creates inefficiencies throughout the whole plant.

And that directly changes cost of goods sold. If the tons per hour through the plant change, so does the cost per ton. From that standpoint, I don’t think there’s anything more important than the blast. It’s also something you can’t go back and fix. Once you fire, you’ve put 50,000 or 100,000 tons on the ground. You don’t get to change a setting and fix just part of it. The blast starts long before the shot fires, and once you begin, you can’t correct it after the fact.

What does a ‘bad blast’ look like in practice? And how does it affect equipment life and production?

Konya: Let me give you a story. I watched a WA600 loader go into a pile with a massive boulder sitting there. The operator is balancing this thing as his back tires are almost coming off the ground. He spends 20 minutes dragging this one boulder away from the face just to get into the shot pile.

First, that kills production. Second, anyone from the equipment side will tell you that’s absolutely not what you want to be doing with a loader. But what choice does that operator have? If the blast produced a huge boulder, he has to deal with it.

But here’s the bigger point: Everyone focuses on boulders because you can see them. What you can’t see is just as important.

Floor quality is a big one. We go to sites where we see undulating floors, and people immediately blame the geology. That’s the easy answer because you can’t recreate the geology afterward, and most people don’t have the technical background to argue with a blaster about how geology affects the blast.

My position is this: The blaster’s job is to overcome the geology – not blame it. If it’s a geologic problem, it’s still the blaster’s responsibility. There are truly rare cases where unusual geology causes something weird to happen, but those are one in a million. Boulders, bad floors – those are things a blaster should be controlling.

Fragmentation matters because the goal isn’t just to ‘get rid of the boulders.’ It’s getting the right size rock so the crushers run efficiently. You want material that feeds well, fractures well and maintains tons per hour. That requires knowing what the blast pattern will produce and having the ability to communicate that to the plant: ‘Here’s what the fragmentation will look like, and here’s what changes if we adjust cost by 10 cents per ton.’

And we can’t ignore drilling. Poor drilling is the biggest risk a blaster faces. If the holes aren’t drilled right, we can’t fix that with explosives.

Technology has really accelerated in drilling and blasting. Where are we today with tools like drones, smart rigs and AI? And how accurate are these models becoming?

Konya: Ten years ago, technology in this space was basically a string with a water bottle, a tape measure and maybe a rangefinder the blaster brought from his hunting bag. That’s where the industry was.

Today, we’re using drones on every shot. We map the terrain, get good 3D models, import blast designs and build accurate burden and spacing data. Smart drills take that survey data, and now the rig knows exactly where it needs to go and how deep to drill. We get penetration rates, real-time drill logs and we can see problems while they’re happening.

That’s been one of the biggest changes: live QA/QC before we ever start loading holes. If a front hole or a back hole is off, we know it immediately and we can call the driller back. That used to be impossible.

Artificial intelligence has also transformed this industry. We can simulate blasts before we fire them – muck piles, throw, flyrock, risk zones. After the shot, we do another drone flight, get real fragmentation data and feed that back into the system so the next simulation is even better. It’s a feedback loop.

Five or six years ago, these models were just a starting point. Today, with the advancements in AI, they’re far more accurate. A junior engineer can now click two buttons and get what would have taken us a day to model 10 years ago.

We’re not at 100 percent accuracy yet, but based on the amount of data coming from smart rigs, surveys, drones and AI processing, I don’t see a reason we won’t get very close in the future. And honestly, at this point reliable blasting companies should already be offering this as standard practice.

Powder factor used to be the go-to metric. You’ve said it’s outdated. What should people be measuring instead?

Konya: Powder factor is an old concept. It goes back to the 1600s, when the Hungarians first started using black powder to break rock and needed a simple way to scale the idea. It was never a design tool. By the 1700s, people already knew it wasn’t effective.

It resurfaced in the 1940s and ’50s, when shock-physics research was happening around nuclear weapons. And in the ’60s and ’70s, it became a great sales tool. Saying ‘double your powder factor’ is a great way to double your explosives bill. It has nothing to do with good blasting.

I’ve seen quarries blasting at three times the powder factor we use and still getting bad results. We reworked one site’s design in a single day and cut their blasting cost by two-thirds while eliminating oversize they’d battled for years.

So powder factor is fine for a greenfield mine firing its first-ever blast. After that, it’s meaningless.

What should we measure instead? The end result. Fragmentation. Vibration. Tons per hour. Equipment life. Environmental impact. Cost per ton of saleable material.

That’s what matters.

What lessons would you pass on to the next generation entering the field?

Konya: For the next generation, my message is: learn and lead.

Learning means using resources like the Pit & Quarry University Handbook, getting training, seeking mentors, reading the research. My advantage was having my father as a mentor, but I still went out and learned everything I could from other experts.

Leadership doesn’t mean you’re the boss. It means you carry yourself the right way.

If a hole needs stemming, pick up the bucket. If you see a safety issue, speak up. Lead from where you are.

And this industry needs you. The average blaster is well past retirement age. There are big gaps to fill. It’s an exciting time to enter the field.

More on drilling & blasting

The brand-new Pit & Quarry University is now available, offering the fundamentals of blast design, drilling techniques and explosives handling. Check out Chapter 3, which is fully dedicated to drilling and blasting, at pitandquarry.com/pqu.

Related: Konya Mining divests construction, industrial minerals assets